Check out these FREE educational resources!

The Need to Go: Toilets and Relief Facilities in WWII Aircraft

by Nathan Huegen, CAF VP of Education

Published 7.16.24

World War II was an exercise in logistics. For the United States, the War was the largest logistics experiment in the country’s history. With troops at sea, on every type of terrain, and in every climate, planning was required down to the smallest detail. Aviation as a major tool of war was a new concept, and many details had to be considered and reworked “on the fly.” This includes provisions for toilets and other relief facilities on board. By most accounts, the options to relieve oneself were not the greatest, so another focus was on minimizing the “need to go.”

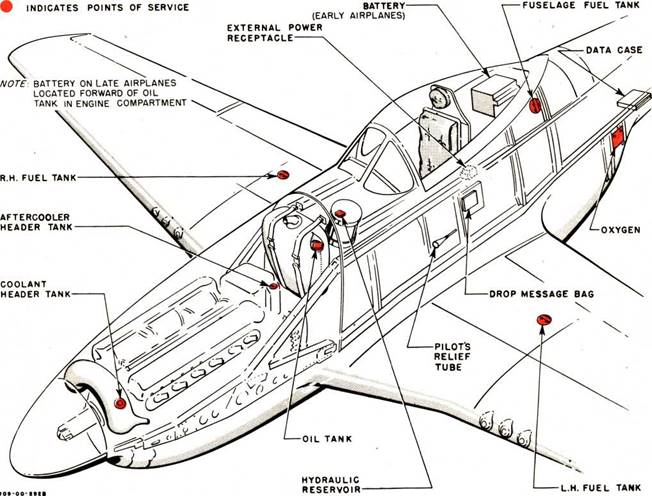

Long-range fighter airplanes often had a relief tube, a funnel located near the seat connected to a tube that ejected the urine into the air. Albert Abraham, a P-51 pilot stationed in India, flew some incredibly long missions, some approaching 8 hours roundtrip from his base to targets inside Thailand and back. After the long missions, he recalled that the ground crew would have to lift him from the airplane after he became numb from sitting in one place for so long. He describes using the relief tube as an “interesting” endeavor. The P-51D “didn’t have much of a relief tube…You’d have to put out a few drops, then hold them back, and go a few more.”

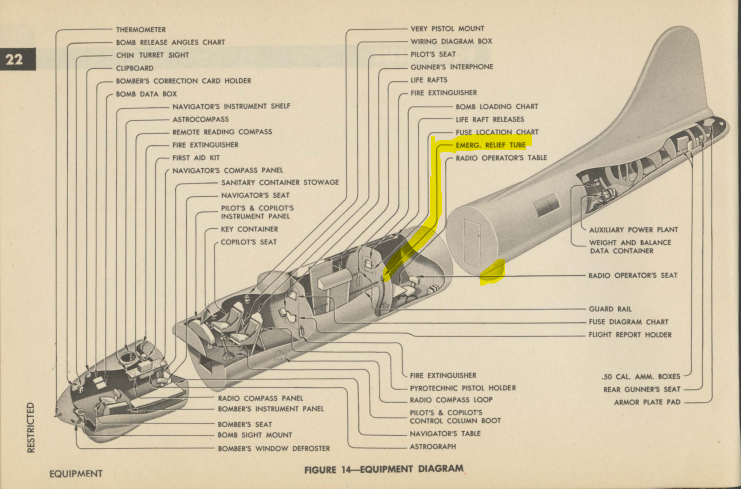

On bomber aircraft, the crew could use a relief tube located in the bomb bay. On the B-17, the relief ejection area was located near the ball turret, which resulted in several harrowing moments for the turret gunner. B-17 navigator Donald Bertholf remembers his turret gunner thinking he had been hit when frozen urine crashed into the plexiglass on a mission over Germany. Sometimes, the liquid would splash on the turret and then freeze in place, hindering visibility.

Bomber aircraft could also have a chemical toilet behind the waist gunners. It was out in the open, but the area near the toilet did have a coat hook and a space for toilet paper. At high altitudes, anyone needing to use the toilet had to carry a portable oxygen bottle with them. Any individual who used the toilet was also responsible for cleaning it. Chemicals in the toilet were supposed to treat the smell, and they featured liners that were supposed to hold the contents for disposal. B-29 radar operator Mason Fitch remembers hitting an updraft on a mission over Japan and hearing the crew of another airplane in his formation talking about the toilet spilling its contents across the floor.

A way to manage the need to go to the bathroom was by planning the airmen’s diet. Anything that could cause excess bloating or gas was removed from their preflight meals. For example, airmen ate real eggs rather than the powdered variety since it was believed they would cause less gastrointestinal distress. Reminders to troops stationed throughout the Pacific cautioned against the local water sources and required the men only to use the treated water provided. Diuretics such as coffee became problematic, but the tension of the flight and the adrenaline of combat led to a lot of sweating. Many airmen discussed a lack of need to use the relief tube on the missions. Others resorted to using a bottle or thermos instead of the relief tube or chemical toilet.

Today’s lavatories on commercial airplanes can be small and cramped, but they have several features unavailable on World War II aircraft, including privacy and a way to flush. The contents of modern aircraft are held in a tank and not ejected toward the gunner in the ball turret. Modern passengers do not have to carry the portable oxygen bottle with them to the lavatory.

In the photos below, you can see the existing relief tube and evacuation point on the Commemorative Air Force's C-45 Bucket of Bolts.

This image shows the bucket-shaped toilet positioned near the waist gunners in the B-17 Flying Fortress.

Image courtesy of the National Museum of the United States Air Force

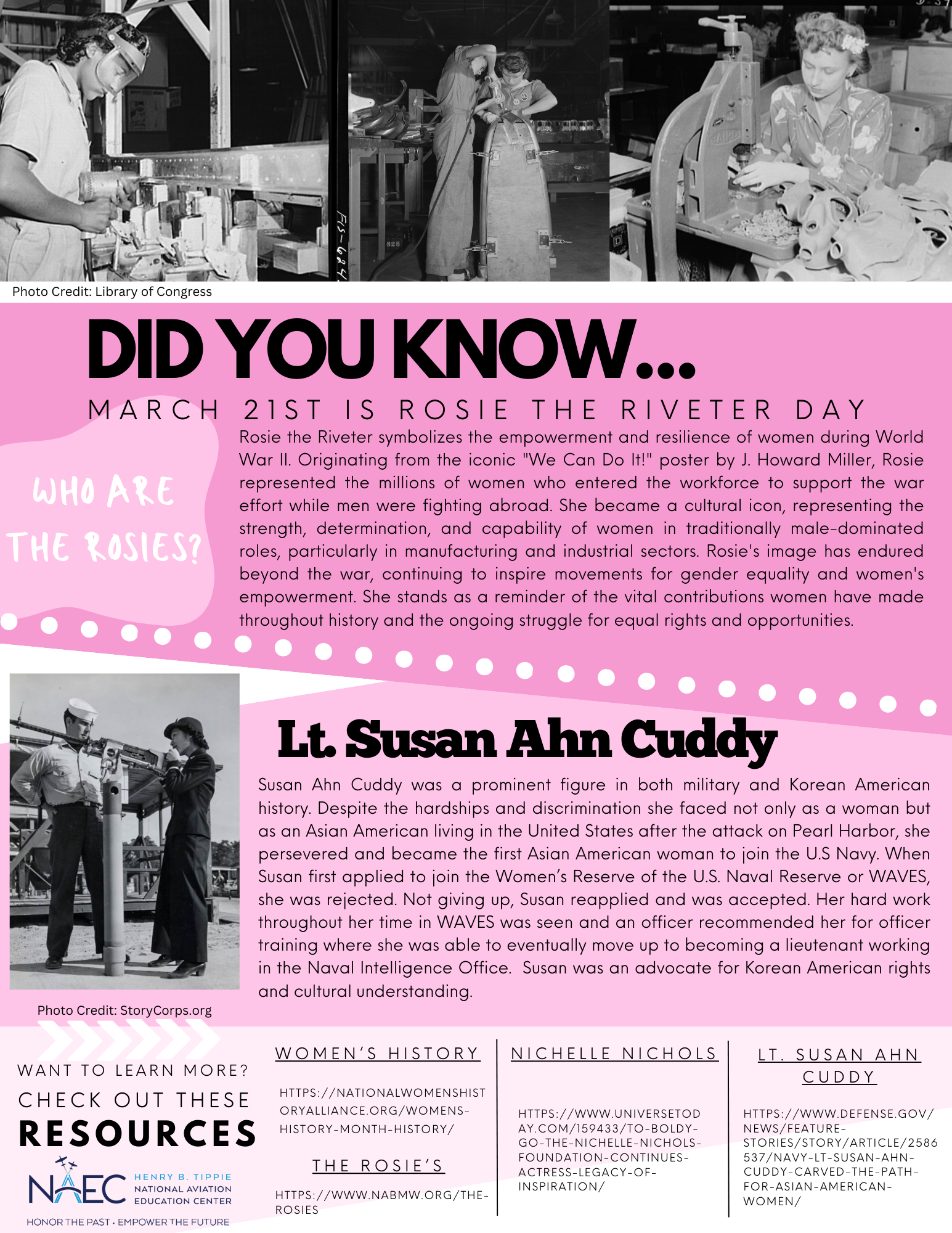

This image shows a diagram of the tail section of a B-17F showing the placement of the toilet paper holder.

This image shows a diagram of a P-51 Mustang showing the location of the Pilot’s Relief Tube.

In this image, you can see the location of the Emergency Relief Tube in a B-17. Note the location of the tube relative to the ball turret.

Ice Cream on the Frontlines: Sweet Treats of World War II

by Nathan Huegen, CAF VP of Education

Published 6.14.24

In every theater of the conflict—If there were Americans, there was ice cream

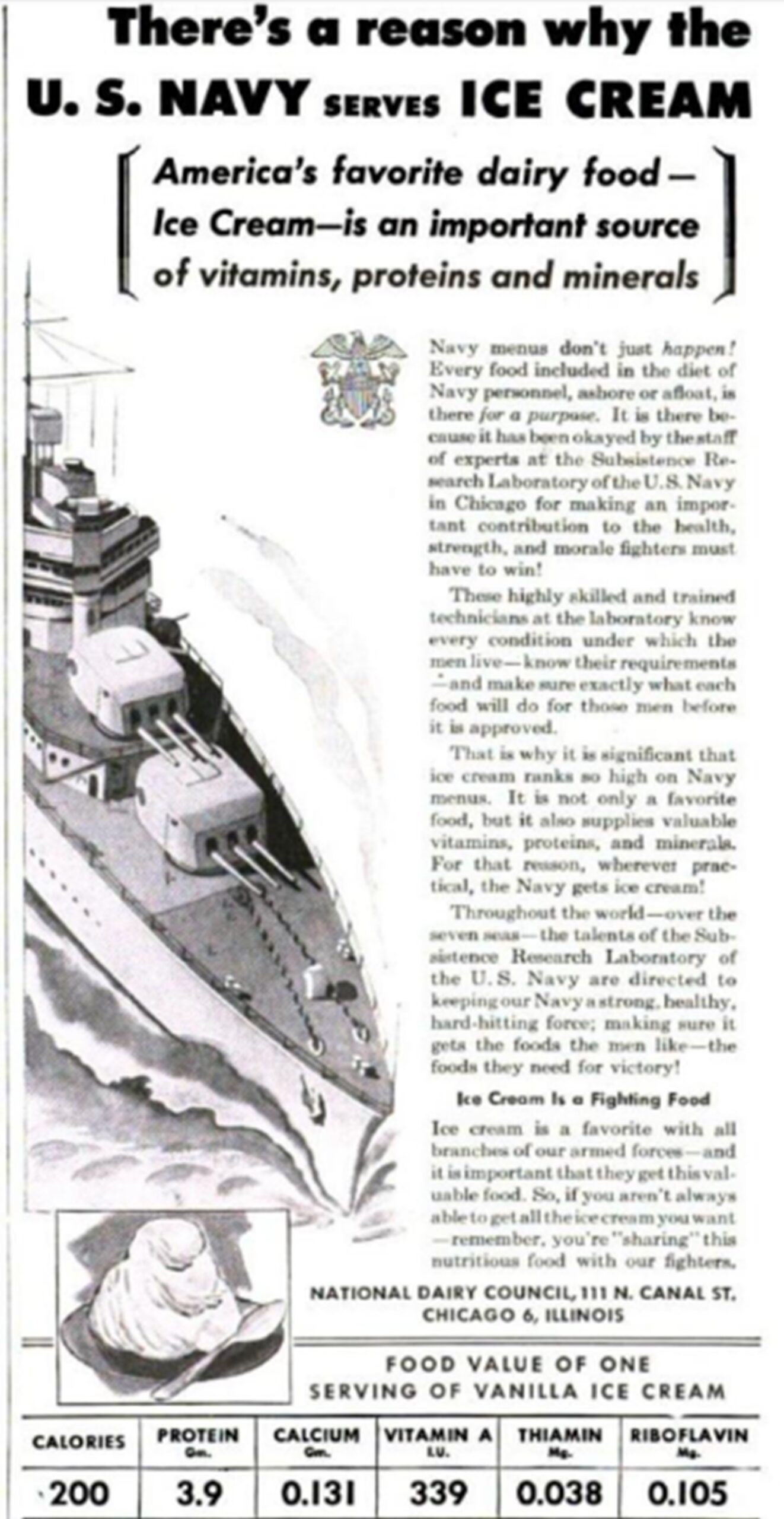

During World War II, ice cream served as an instant morale boost wherever it was found, and the military invested a great deal of time and money into procuring, creating, and distributing the sweet treat. A gathering with ice cream infused the event with optimism and led to smiles all around. For the service members, locating ice cream had much to do with geographic location, branch of service, duties, and a little luck.

The U.S. Navy had regular access to ice cream, at least on the larger ships. Some cargo ships even had sailors dedicated to operating ice cream machines that could churn out 5 gallons per batch and around 15 gallons per day. Melvin Munch, a sailor on the USS Rankin (AKA-103), described attending “ice cream school” while en route from Okinawa to Saipan toward the end of the War. After a few hours of training, he was awarded a diploma declaring him an official ice cream maker. He kept that diploma for the rest of his life.

Although tempting, the Navy kept only some ice cream for themselves. The ships would bring it to shore, and officers would even try to get it delivered to the front lines. The Navy purchased a concrete barge for $1 million and converted it into a floating ice cream factory to ship in large quantities. The barge, dedicated solely to ice cream, could churn out 10 gallons in just seven minutes. The barge’s appearance proved very popular throughout the Pacific, relieving soldiers and Marines growing tired of their “alphabet rations.”

One location that ships could not reach was China. The Japanese controlled the coast and all Chinese ports; therefore, supplying the interior took a lot of work. Arriving by air over the Himalayas, each piece of cargo was precious. Even then, ice cream made its way to the American lines. In Kunming, one state-of-the-art ice cream machine—the only one in the country—supplied enough ice cream to the 14th Air Force to offer each man a few scoops once every ten days.

At times, the American production of ice cream seemed extravagant to the local population. In 1942, the British government temporarily banned ice cream from American forces. Their rationale was that the British soldiers did not have ice cream, and children throughout the country went without it. The British Food Ministry said the ban would “free men for service, release refrigerating equipment, and save paper.” The ban was unpopular, and ice cream soon returned to the airfields and training bases.

In the meantime, American airmen were experimenting with making ice cream inside their bombers. Mixing the ingredients in a large can and hanging it in the rear gunner’s compartment, the crew had a nicely frozen and shaken treat at the end of a mission. Early attempts saw the airmen place the cans too close to the engines, where the heat resulted in a slushy product. The aircraft's rear hit the perfect temperature for a consistently frozen product. The process was repeated worldwide in various bombers, cargo, and transport airplanes.

As the War drew to a close, access to ice cream improved. The rationing of milk, eggs, and other essential ingredients was less severe. Enterprising locals in Italy, the Philippines, and Okinawa found they could earn money selling ice cream to the remaining Americans. Children deprived of almost all sweet treats often begged for a few bites. Still, for nearly every American, no amount of foreign ice cream could compare to that first scoop on the streets on any Main Street in the USA.

Photos from the National Archives and Records Administration

In this image is the lone ice cream machine in Kunming, China. This machine ensured each member of the 14th Air Force could have ice cream every ten days.

In this image, American airmen host a Christmas party for the sons and daughters of British soldiers in December 1943.

This is a clipping from the National Dairy Council Advertisement in the March 1944 edition of Hygeia Magazine – a publication of the American Medical Association.

In the heat of the tropics - Ice cream was even sweeter. In this image, ice cream is dished out in Mindoro, Philippines.

In this image, Paratroopers with the 82nd Airborne pause for ice cream in Palermo, Sicily.

Recovering American Soldiers crowd the bar waiting for ice cream at a hospital in Paris.

In this image, Black soldiers take a break from service in India for an ice cream treat.

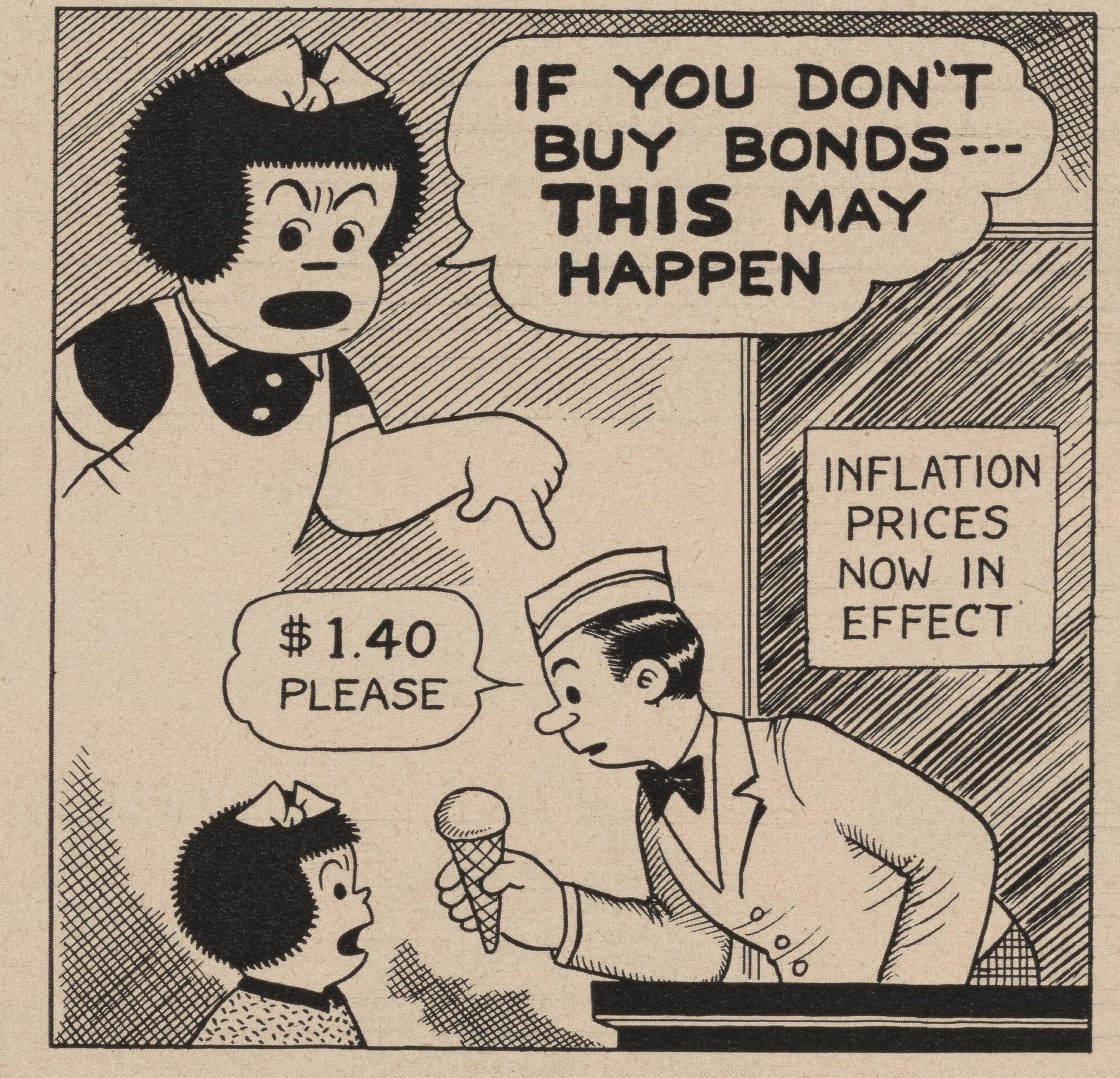

Ice cream prices were used as motivation to buy war bonds. This image was included with a poster urging students to buy war bonds to do their part to support the war and to keep inflation at bay.

Heroism and Honor in the Pacific Theater

by Nathan Huegen, CAF VP of Education

Published 5.15.24

World War II disrupted and transformed societies throughout Asia and the Pacific. The brutality of the war devastated families and destroyed entire cities, nations, and cultures. Through the devastation, stories of survival and heroism emerged from the wreckage.

Josefa Llanes Escoda, Aiding Prisoners of War

The United States accessioned the Philippines after victory over Spain in the Spanish-American War in 1898. Josefa Llanes Escoda was born this same year, and she experienced many of the imported American customs in the Philippines. After graduating from the Philippine Normal School in Manila, she joined the Philippine Chapter of the Red Cross. She then left the Philippines to attend Columbia University, earning a master’s Degree in Sociology in 1925. Her time in the United States introduced her to the suffragette movement, and she brought those organizing principles to the Philippines. Although the Philippines was subject to the United States, the country was moving toward independence, which began in 1946.

Escoda returned to the Philippines in the late 1930s. As she fought for women’s suffrage and established the Girl Scouts of the Philippines, officials in Manila were monitoring developments elsewhere in Asia. The Japanese war machine was on the march through China, and newspapers around the world documented the brutality of the Japanese Army. US negotiators demanded that Japan relinquish their gains in China and pursue a peace process. Japan refused the demands and unleashed attacks on Chinese civilians. Military commanders in the Philippines drew up contingency plans in the event of a Japanese attack.

On December 8, 1942, Japanese planes bombed bases in the Philippines as a landing force prepared for an all-out attack. General Douglas MacArthur declared Manila an open city, and his forces moved to defensive positions in Bataan and Corregidor, where they held out until May 1942. The surrenders of Bataan in April and Corregidor in May formed the largest surrender of American forces in history. This resulted in a brutal death march and a humanitarian crisis in the prison camps.

Escoda and her husband Antonio worked to provide medicine, food, and clothing to the prison camps. They would also relay messages to and from the camps. The Japanese grew suspicious of the Escodas’ actions and arrested the couple. Josefa Llanes Escoda was last seen alive in January 1945. Josefa Llanes Escoda is renowned for her civic activities and World War II duties in the Philippines. From 1991-2022, Escoda was featured on the Philippines 1,000 Peso bill along with fellow World War II heroes Vicente Lim and Jose Abad Santos. The year 1998 was proclaimed as Josefa Llanes Escoda Centennial year by President Fidel Ramos.

Josefa Llanes Escoda with a group of Girl Scouts. Escoda was the founder and first National Executive of the Girl Scouts in the Philippines.

Josefa Llannes Escoda appeared on the Philippines 1,000 Peso bill along with fellow WWII heroes Vicente Lim and Jose Abad Santos.

Jacob Vouza, A Scout for the Marines

Sir Jacob Vouza was born on the island of Guadalcanal around 1892 just as the British Solomon Islands Protectorate began to govern the islands. The British hoped to develop profitable coconut plantations on Guadalcanal, but they never established a large military presence. Few Europeans inhabited the islands with just a handful of plantation owners, businessmen, and missionaries living scattered among the islands. Providing security for the business interests fell to locals such as Vouza who began working for the Solomon Islands Protectorate Armed Constabulary 1916.

In 1942, the Japanese arrived in Guadalcanal mostly unopposed. Most of the initial Japanese soldiers were construction workers with orders to build an airstrip that, when completed, would put their bombers in range of the major cities on Australia’s east coast. The Allies countered the Japanese on August 7, 1942 as the 1st Marine Division landed on Guadalcanal in the first American offensive of World War II. Vouza, who had volunteered with the Coastwatchers, rescued a downed pilot during the opening days of the operation. Escorting the aviator to the American lines, Vouza first met American Marines.

Two weeks later, Vouza was scouting for Japanese outposts in the jungle when he was captured. A small American flag in his loincloth gave him away, and the Japanese tied him to a tree and tortured him, hoping to find information on the American forces. Vouza refused to cooperate with his captors, and he managed to chew through the ropes. Crawling through dense jungle to the American lines, Vouza warned the Marines that a force of several hundred Japanese were on their way to attack their position. Once recovered from his injuries, Vouza returned to action with the Marines.

For his service in World War II, Jacob Vouza received the Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire along with the Silver Star and Legion of Merit from the United States. A statue of Vouza appears along the main road in the capital of the Solomon Islands, and his family continues to support remembrance ceremonies in Guadalcanal.

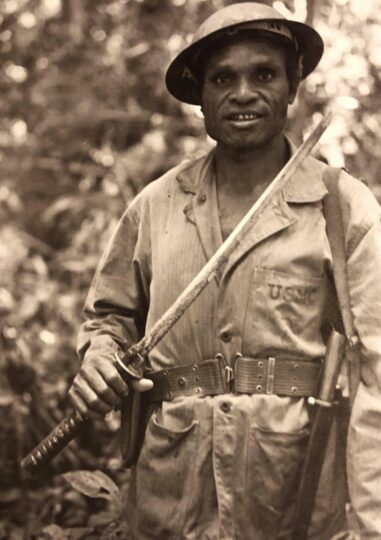

Jacob Vouza posing in his Marine uniform during the Battle of Guadalcanal.

Sefanaia Sukanaivalu, Recipient of the Victoria Cross

Sefanaia Sukanaivalu was born in Fiji in 1918, just a few generations after the British annexed the Kingdom of Fiji in 1874. Under the British, local rule in Fiji remained under the domain of chiefs, and Fiji raised its own military in both World War I and World War II. His name, Sukanaivalu, means “return from war.” His birth coincided with the return of his island chief from France during World War I. Sukanaivalu enlisted in the Fiji Infantry Regiment, which was placed under the command of the United States. The Fijian soldiers served throughout the Solomon Islands campaign from Guadalcanal to Bougainville.

On June 23, 1944, Sukanaivalu was on a patrol on the west coast of Bougainville when Japanese soldiers ambushed his unit. Sukanaivalu crawled forward to rescue some wounded men when the Japanese again attacked. Sukanaivalu rescued two men but was seriously wounded. Rescue attempts were made, but each attempt resulted in heavy Japanese fire. Rather than risk the lives of his fellow soldiers, Sukanaivalu rose up and exposed himself to the Japanese guns. Sukanaivalu was killed, but his patrol was able to retreat to a safe position.

Sukanaivalu is the only Fijian to receive the Victoria Cross, the highest military award in the British Honours System. A mural of him adorns the city hall in the capital city of Suva. His final resting place is at the Bita Paka Commonwealth Cemetery near Rabaul, but plans have been announced for the repatriation of his remains to Fiji.

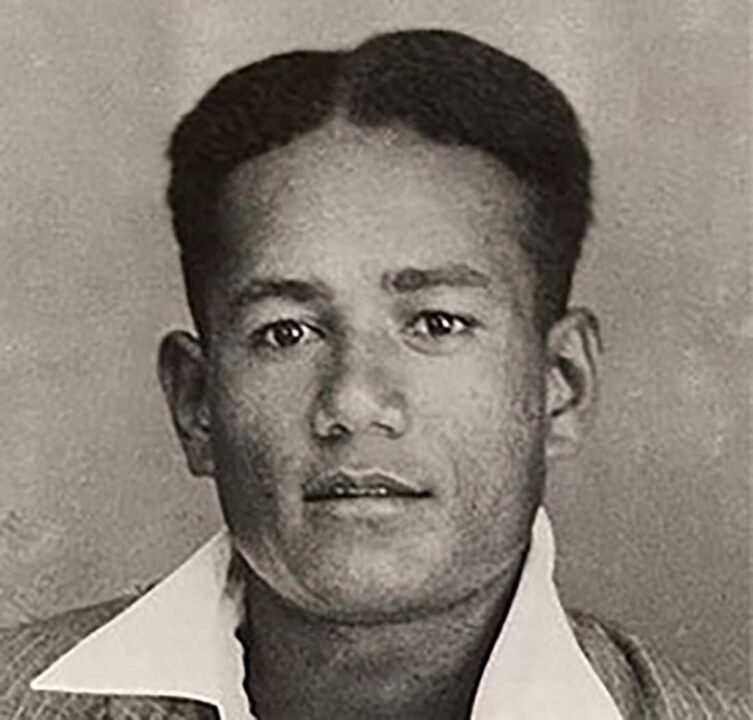

Sefanaia Sukanaivalu prior to enlistment

Kimiuo Aisek, Living with the Japanese

At the outbreak of the War, Kimiuo Aisek was a teenager in Truk Lagoon, now called Chuuk. Born during the time of the Japanese mandate over the islands that began in 1919, Aisek learned to speak Japanese and to become a good “child of the emperor.” He was usually quick to scale a coconut tree at the request of a thirsty Japanese official, and he found favor with a sailor named Uchida.

On February 17, 1944, the American attack on Truk, Operation Hailstone, began. Three carrier task groups launched over 500 aircraft in a massive operation to destroy the Japanese base. Aisek and his family took refuge in a cave before curiosity took over and he wandered outside to watch the bombing. He remembers watching the explosion of the Aikoku Maru, a ship he frequented when he would deliver cargo for the Japanese.

In 1945, the United States began repatriating the Japanese and administering the islands under a United Nations Mandate. Aisek found the Americans strange, but he slowly learned English and found work on the cargo ships operating between Truk and the Mariana Islands. He later lived in Hawaii to train in commercial fishing. By 1972, Aisek was working as a diver in the Department of Fisheries in Truk when a renewed attention to the Japanese shipwrecks brought “wreck-divers” to the lagoon.

Aisek found a new calling in assisting the divers with their tanks and in providing guidance on the islands. He was so skilled and personable that many of the divers asked when he would open his own dive shop. On November 13, 1973, Kimiuo Aisek opened Blue Lagoon Dive Shop, the first of its kind in Truk. Aisek personally escorted many divers to the wrecks in the Lagoon. The dive shop became wildly successful, purchasing the former Continental Hotel in 1998. Nearly every map and guidebook to the Japanese wrecks of Truk Lagoon can be traced to the efforts of Kimiuo Aisek.

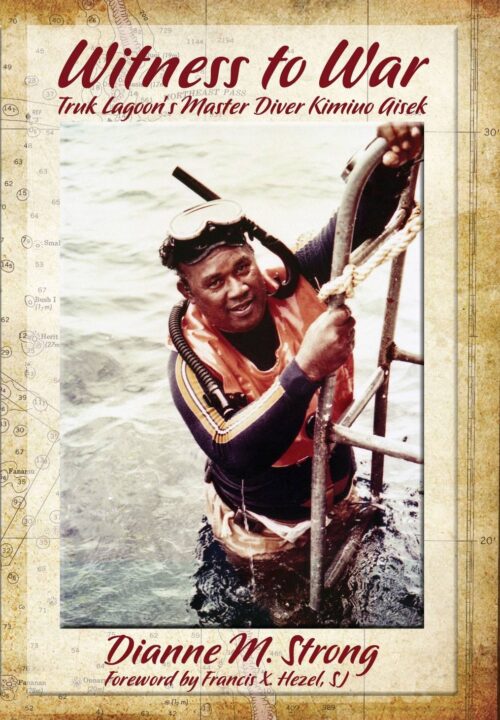

Kimiuo Aisek’s life story is told in a book by Dianne Strong

Beryl Owens Paschich: A WASP Pioneer

by Nathan Huegen, CAF VP of Education

Published 4.12.24

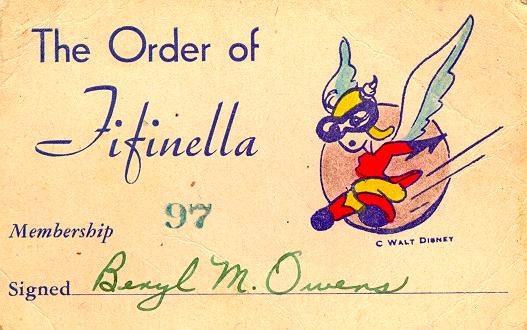

“Watch your air speed. Watch your air speed.” Beryl Owens’ assigned flight instructor on the AT-6 was fond of saying “watch your air speed,” but Owens did not know what to do with her air speed when she “watched it.” Frustrated, she went to her mentor, a civilian flight instructor who had taken her under his wing. She told him she had not figured out how to correct the air speed to the instructor’s liking and asked him what she should do. A short response came from her mentor. “Ask for a change of instructor.”

Owens received a new instructor, a short man who had to sit on four cushions inside the AT-6, and she finished her training. This experience summarizes Owens’ experience as a WASP. She was always progressing even if an obstacle came her way.

Owens began her journey as a pilot in San Antonio, TX when she was a volunteer with the Ground Observer Corps. She noticed a sign asking, “All women interested in flying or aviation come to a meeting of the Texas Wing of Women Flyers.” Owens joined the group she referred to as a “flying club” of “maybe 12 to 15” members. The group invited Jacqueline Cochran, the head of the Women Army Service Pilots (WASP) to speak. Owens was hooked. She worked to get her flight hours up to the standard and applied for entry.

Owens met her first obstacle with the application. Other women she knew had been accepted for training, but Owens had not heard from Cochran or anyone with the WASP. Fortunately, a friend she met in Washington, DC had become Cochran’s secretary. Owens wrote a letter asking, “what’s happened to my application?” Her friend searched, and found it buried on Cochran’s desk. She was accepted for training.

Upon arrival to the training field in Sweetwater, TX, Owens received her uniform— “mechanic’s overalls…the olive drab ones and they were like ten sizes too big.” The women jokingly referred to them as “zoot suits,” referencing the baggy suits that had been trendy among African American and Latino men. The “really swanky uniforms” would have to wait until graduation.

During her training, Owens flew the PT-19, Stearman, AT-6, and BT-13. She hoped to fly a B-26, but every time she got close, the assignment changed. She spent most of her time as a pilot at Majors Field in Greenville, TX. At the field, she would pilot BT-13s that had undergone repair. An observer would fly with her in the repaired aircraft. “They would take some tape and a piece of string about two feet long, maybe 18”, and tape these pieces of string all over the wings and the flying surfaces at maybe a foot apart…they would watch and if there were eddies when those strings went around they knew there was something wrong in that spot.”

After the WASP were disbanded on December 20, 1944, Owens applied for a job with the FAA. She continued in that position until she married a fellow FAA employee, Jack Paschich. She resigned due to the FAA’s anti-nepotism policies, noting that “he might be my supervisor and that would never do, but it’s not that I would ever be his supervisor.” Beryl Owens Paschich received her honorable discharge in 1979 after the WASP were officially named an active duty military unit in legislation signed in 1977.

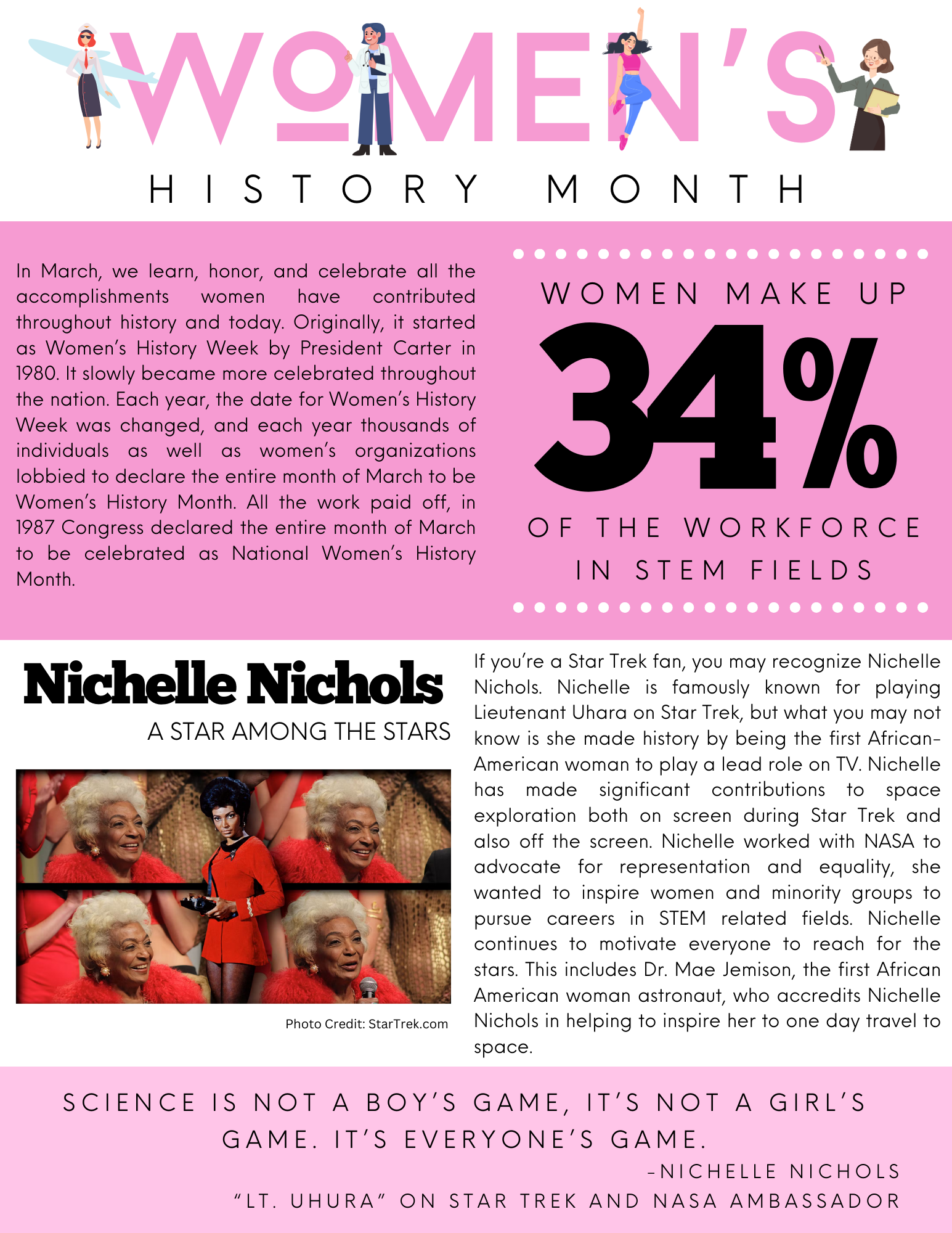

Women in STEAM Infographic

An infographic for Women's History Month

by NAEC Education Team

Published 3.13.24

Click to download

Supplying the Air War at Wright Field

Elizabeth S. Stark Oral History

by Nathan Huegen, CAF VP of Education

Published 3.12.24

On Friday, March 13, 1942, twenty-two-year-old Elizabeth Stark received the surprise of her young life. Upon reporting to Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio, Stark found that she was eligible for a permanent civil service appointment. Her new clerical job at Wright Field was not simply for the duration of the war, it was a career. Aside from her new duties as a stenographer, filling out forms with carbon copies 15 deep, there was much for Stark to do. Finding a place to live, forming a social circle, and searching for the best places to eat were high on her list. A move to Dayton from her home in Bowling Green, Kentucky was anything but routine in 1942. Dayton, as the new air logistics hub, was booming. Wright Field employment soared from 3,700 in 1939 to a peak of over 50,000.

Wright Field and neighboring Patterson Field buzzed with activity round-the-clock. Workers entered and departed at all hours. Construction crews worked feverishly in expanding the base from 40 buildings to more than 300. From her post, Stark remembers that the construction was “chaos, because the building wasn’t completed, and we were operating on wartime, which meant we went to work in the dark most of the time.” To reach the building, she crossed “a large area with boards across it…underneath the board were mud and all sorts of trash. You didn’t dare fall off the board.” The workdays were long and frequent. Stark recalls, “we were required to work six days, eight hours a day at least. I think every other week we worked Sunday also.”

After a few weeks as a stenographer, Stark caught the eye of a civil engineer from Air Materiel Command, and she accepted a job as his assistant. She did most of his writing and reporting while also working on some of her own projects under his supervision. The work done by Stark and her colleagues was instrumental in the conduct of the air war. Supplying air crews was a new task, and procedures started with basic projections of troop movements. Initial forecasts for supplies were based on six-month forecasts of deployments, but the needs of the airmen and the supplies they received rarely synchronized.

Stark and her colleagues adjusted as the war progressed. As the air crews completed their missions and the mechanics kept the planes flying, the number of supplies needed per aircraft became clear. Materiel Command could anticipate the number of jacks, tools, and equipment to route with the new aircraft. As depots around the country became better organized, the flow of logistics improved. Her team felt like a well-oiled machine, and Stark developed a close bond with her colleagues that extended to leisure activities like a softball league.

When the war ended, Stark had mixed emotions. “I can remember that everybody had left on VJ Day, and I went home. You were supposed to out celebrating, I guess, but I had a funny, way-down feeling that maybe this was one of the greatest experiences of my life, and it was coming to an end. I’m sure there were a lot of other people in the service who had the same feeling because a lot of people came from nowhere and this was the first time they had been able to do something.”

Stark remained at the newly christened Wright-Patterson Air Force Base after the war, working in Curtis Lemay’s Strategic Air Command. She met Lemay several times and found him very “demanding” and that he “had a lot of ideas that I didn’t agree with.” After a few years of seeing more and more men with less qualifications come in with jobs above her, she asked if she would be

in the running for a promotion. She didn’t like the response, so she followed a previous supervisor to a new position in the Pentagon in 1954, and later took a job with a bank to help lead the shift to computerized banking.

Reflecting on her time at Wright-Patterson, Stark says that she “gained confidence in my ability to do something…Working there and being able to walk in and talk to a major general or lieutenant general and give presentations in front of them did something for my confidence. I took those skills to Washington, D.C. and eventually to the savings and loan.”

Wright Field in the 1930s before the massive expansion during World War II. Elizabeth Stark was one among the tens of thousands of civil workers employed at Wright Field during WWII. In 1948, Wright Field merged with neighboring Patterson Field to become Wright-Patterson Air Force Base.

In October 1945, an Air Forces Fair was held at Wright Field. Attendees came to marvel at the fleet of American aircraft and curiosities like a captured German V-2 Rocket. Elizabeth Stark continued her employment at Wright-Patterson with Strategic Air Command.

Images courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Master of the Air Part 1

Donald F. Bertholf Oral History

by Nathan Huegen, CAF VP of Education

Published 2.14.24

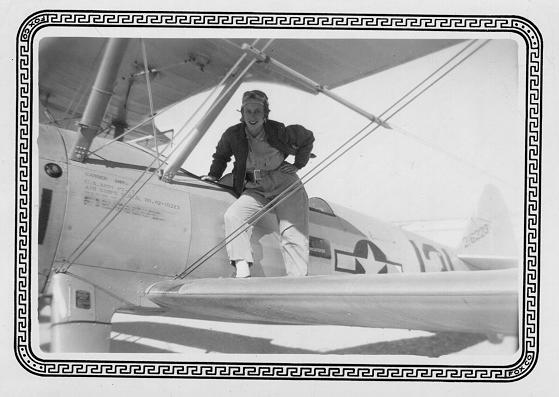

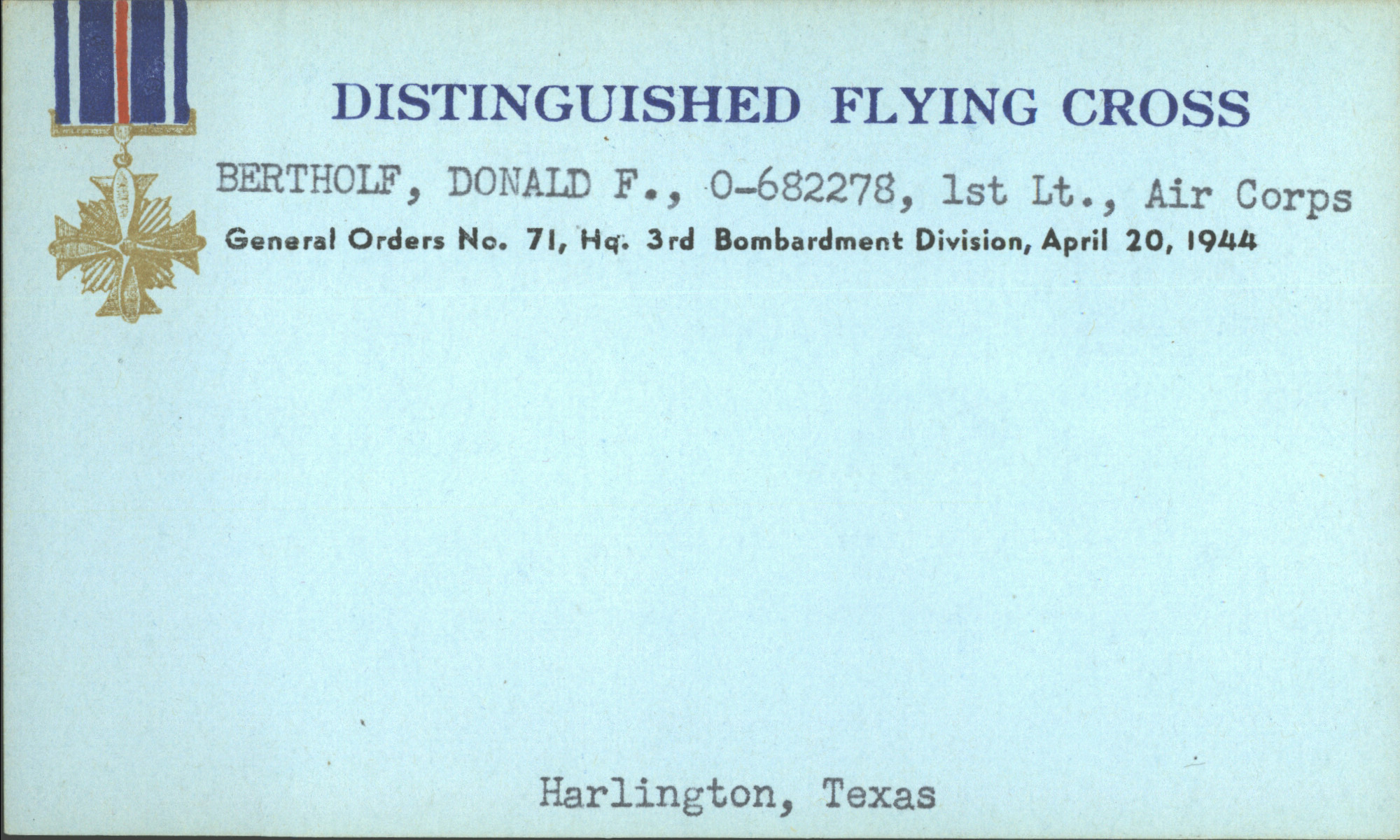

Masters of the Air, released last week on Apple TV+, highlights the experiences of the 100th Bomb Group. The 100th received the nickname, “The Bloody Hundredth” due to severe losses encountered during its early missions. The Oral History Project housed at the Henry B. Tippie National Aviation Education Center (NAEC) features stories from many of the crewman who served in the 8th Air Force. This month, we focus on Donald F Bertholf of Harlingen, TX who served as a navigator in the 100th, and his experience over three days during “Black Week” in October 1943.

On October 8, 1943, Bertholf’s string of missions began with a raid on shipyards near Bremen on the northern coast of Germany. The antiaircraft fire was thick. Bertholf recalls, “it’s just like you read, just like you read in the books, you know, or see in the movies or something’ and here we are, right in the middle of it. And we got through it…we got a whole bunch of hits that they had to fix.” On the success of the mission, Bertholf remarked “probably not” when asked if he hit the target. The flak was too great, and the altitude was too high.

The next day, Bertholf flew to Marienburg to bomb an aircraft factory. This would be the farthest mission undertaken to date, and they would bomb from 12,000 feet rather than the 25,000 at Bremen. We “creamed ‘em,” Bertholf remembers. Photos showed direct hits throughout the target area. Leadership from Bomber Command all the way up to Winston Churchill sent their congratulations to the units involved.

On October 10, in an ambitious undertaking, the 100th was ordered out for the third day in a row. The target was Munster. Of the 18 aircraft assigned from the 100th, one did not take off, four—including Bertholf’s—returned due to mechanical issues, and twelve were lost over Munster. Only one plane returned from Munster. A B-17 nicknamed Royal Flush piloted by Robert “Rosie” Rosenthal. From the 100th Bomb Group alone, Eighty-two men were captured and 37 killed. Losses at that rate would quickly become unsustainable for the 8th Air Force.

When Bertholf first arrived in England in September 1943, he heard a rumor about the 100th. “All they do is fly submarine patrols.” After Black Week, Bertholf saw the man who uttered the rumor. Not holding back, Bertholf said, “you S.O.B! Where is this submarine patrol business?”

A reconnaissance photo showing the aftermath of the Marienburg Raid. Only one building escaped a direct hit. Lt. General Ira Eaker called Marienburg “a perfect job” and “a day to remember in the air war.”

There are little to no photos available of Bertholf but there is this card noting his award of the Distinguished Flying Cross that misspelled Harlingen, TX as Harlington, TX.