Check out these FREE educational resources!

Beryl Owens Paschich: A WASP Pioneer

by Nathan Huegen, CAF VP of Education

Published 4.12.24

“Watch your air speed. Watch your air speed.” Beryl Owens’ assigned flight instructor on the AT-6 was fond of saying “watch your air speed,” but Owens did not know what to do with her air speed when she “watched it.” Frustrated, she went to her mentor, a civilian flight instructor who had taken her under his wing. She told him she had not figured out how to correct the air speed to the instructor’s liking and asked him what she should do. A short response came from her mentor. “Ask for a change of instructor.”

Owens received a new instructor, a short man who had to sit on four cushions inside the AT-6, and she finished her training. This experience summarizes Owens’ experience as a WASP. She was always progressing even if an obstacle came her way.

Owens began her journey as a pilot in San Antonio, TX when she was a volunteer with the Ground Observer Corps. She noticed a sign asking, “All women interested in flying or aviation come to a meeting of the Texas Wing of Women Flyers.” Owens joined the group she referred to as a “flying club” of “maybe 12 to 15” members. The group invited Jacqueline Cochran, the head of the Women Army Service Pilots (WASP) to speak. Owens was hooked. She worked to get her flight hours up to the standard and applied for entry.

Owens met her first obstacle with the application. Other women she knew had been accepted for training, but Owens had not heard from Cochran or anyone with the WASP. Fortunately, a friend she met in Washington, DC had become Cochran’s secretary. Owens wrote a letter asking, “what’s happened to my application?” Her friend searched, and found it buried on Cochran’s desk. She was accepted for training.

Upon arrival to the training field in Sweetwater, TX, Owens received her uniform— “mechanic’s overalls…the olive drab ones and they were like ten sizes too big.” The women jokingly referred to them as “zoot suits,” referencing the baggy suits that had been trendy among African American and Latino men. The “really swanky uniforms” would have to wait until graduation.

During her training, Owens flew the PT-19, Stearman, AT-6, and BT-13. She hoped to fly a B-26, but every time she got close, the assignment changed. She spent most of her time as a pilot at Majors Field in Greenville, TX. At the field, she would pilot BT-13s that had undergone repair. An observer would fly with her in the repaired aircraft. “They would take some tape and a piece of string about two feet long, maybe 18”, and tape these pieces of string all over the wings and the flying surfaces at maybe a foot apart…they would watch and if there were eddies when those strings went around they knew there was something wrong in that spot.”

After the WASP were disbanded on December 20, 1944, Owens applied for a job with the FAA. She continued in that position until she married a fellow FAA employee, Jack Paschich. She resigned due to the FAA’s anti-nepotism policies, noting that “he might be my supervisor and that would never do, but it’s not that I would ever be his supervisor.” Beryl Owens Paschich received her honorable discharge in 1979 after the WASP were officially named an active duty military unit in legislation signed in 1977.

Women in STEAM Infographic

An infographic for Women's History Month

by NAEC Education Team

Published 3.13.24

Click to download

Supplying the Air War at Wright Field

Elizabeth S. Stark Oral History

by Nathan Huegen, CAF VP of Education

Published 3.12.24

On Friday, March 13, 1942, twenty-two-year-old Elizabeth Stark received the surprise of her young life. Upon reporting to Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio, Stark found that she was eligible for a permanent civil service appointment. Her new clerical job at Wright Field was not simply for the duration of the war, it was a career. Aside from her new duties as a stenographer, filling out forms with carbon copies 15 deep, there was much for Stark to do. Finding a place to live, forming a social circle, and searching for the best places to eat were high on her list. A move to Dayton from her home in Bowling Green, Kentucky was anything but routine in 1942. Dayton, as the new air logistics hub, was booming. Wright Field employment soared from 3,700 in 1939 to a peak of over 50,000.

Wright Field and neighboring Patterson Field buzzed with activity round-the-clock. Workers entered and departed at all hours. Construction crews worked feverishly in expanding the base from 40 buildings to more than 300. From her post, Stark remembers that the construction was “chaos, because the building wasn’t completed, and we were operating on wartime, which meant we went to work in the dark most of the time.” To reach the building, she crossed “a large area with boards across it…underneath the board were mud and all sorts of trash. You didn’t dare fall off the board.” The workdays were long and frequent. Stark recalls, “we were required to work six days, eight hours a day at least. I think every other week we worked Sunday also.”

After a few weeks as a stenographer, Stark caught the eye of a civil engineer from Air Materiel Command, and she accepted a job as his assistant. She did most of his writing and reporting while also working on some of her own projects under his supervision. The work done by Stark and her colleagues was instrumental in the conduct of the air war. Supplying air crews was a new task, and procedures started with basic projections of troop movements. Initial forecasts for supplies were based on six-month forecasts of deployments, but the needs of the airmen and the supplies they received rarely synchronized.

Stark and her colleagues adjusted as the war progressed. As the air crews completed their missions and the mechanics kept the planes flying, the number of supplies needed per aircraft became clear. Materiel Command could anticipate the number of jacks, tools, and equipment to route with the new aircraft. As depots around the country became better organized, the flow of logistics improved. Her team felt like a well-oiled machine, and Stark developed a close bond with her colleagues that extended to leisure activities like a softball league.

When the war ended, Stark had mixed emotions. “I can remember that everybody had left on VJ Day, and I went home. You were supposed to out celebrating, I guess, but I had a funny, way-down feeling that maybe this was one of the greatest experiences of my life, and it was coming to an end. I’m sure there were a lot of other people in the service who had the same feeling because a lot of people came from nowhere and this was the first time they had been able to do something.”

Stark remained at the newly christened Wright-Patterson Air Force Base after the war, working in Curtis Lemay’s Strategic Air Command. She met Lemay several times and found him very “demanding” and that he “had a lot of ideas that I didn’t agree with.” After a few years of seeing more and more men with less qualifications come in with jobs above her, she asked if she would be

in the running for a promotion. She didn’t like the response, so she followed a previous supervisor to a new position in the Pentagon in 1954, and later took a job with a bank to help lead the shift to computerized banking.

Reflecting on her time at Wright-Patterson, Stark says that she “gained confidence in my ability to do something…Working there and being able to walk in and talk to a major general or lieutenant general and give presentations in front of them did something for my confidence. I took those skills to Washington, D.C. and eventually to the savings and loan.”

Wright Field in the 1930s before the massive expansion during World War II. Elizabeth Stark was one among the tens of thousands of civil workers employed at Wright Field during WWII. In 1948, Wright Field merged with neighboring Patterson Field to become Wright-Patterson Air Force Base.

In October 1945, an Air Forces Fair was held at Wright Field. Attendees came to marvel at the fleet of American aircraft and curiosities like a captured German V-2 Rocket. Elizabeth Stark continued her employment at Wright-Patterson with Strategic Air Command.

Images courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Master of the Air Part 1

Donald F. Bertholf Oral History

by Nathan Huegen, CAF VP of Education

Published 2.14.24

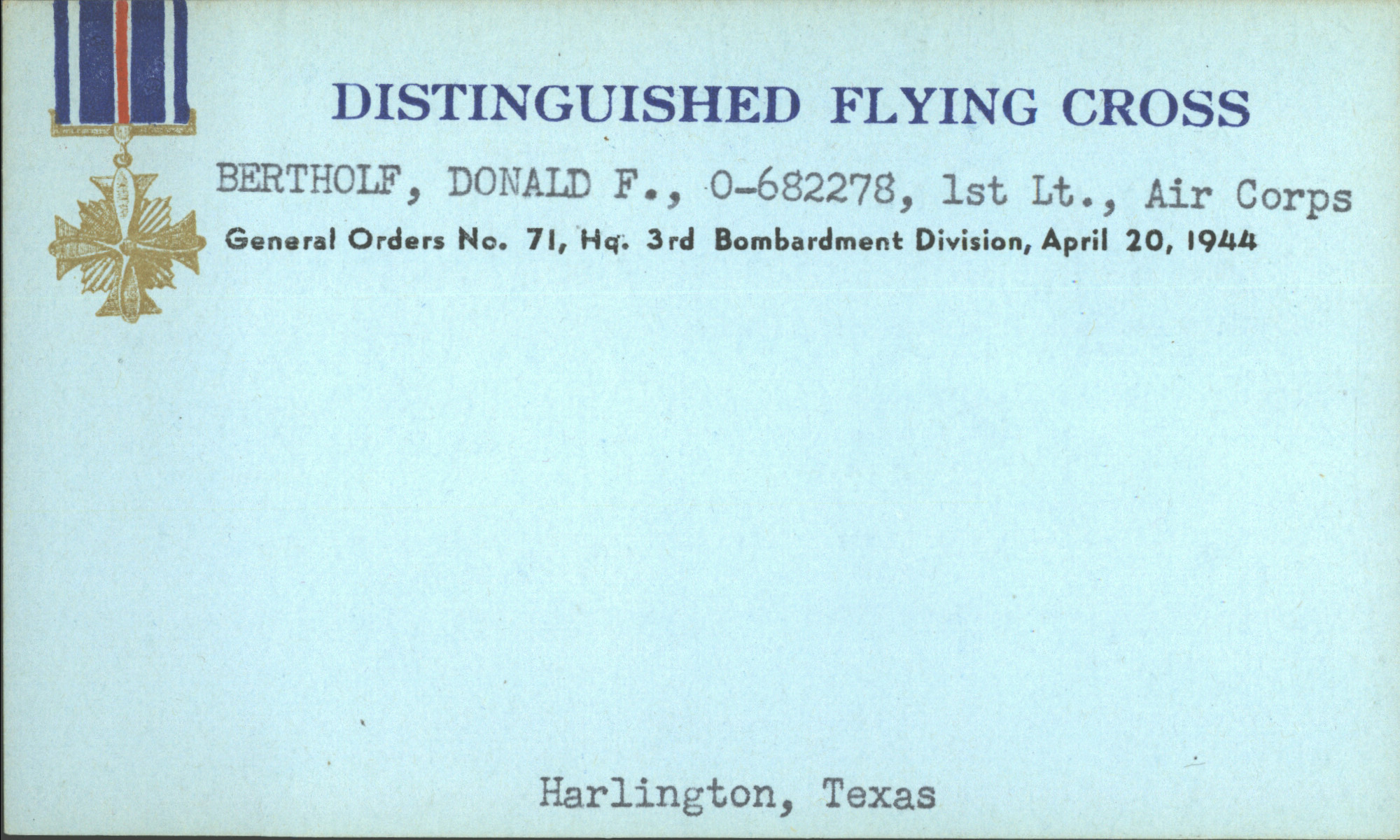

Masters of the Air, released last week on Apple TV+, highlights the experiences of the 100th Bomb Group. The 100th received the nickname, “The Bloody Hundredth” due to severe losses encountered during its early missions. The Oral History Project housed at the Henry B. Tippie National Aviation Education Center (NAEC) features stories from many of the crewman who served in the 8th Air Force. This month, we focus on Donald F Bertholf of Harlingen, TX who served as a navigator in the 100th, and his experience over three days during “Black Week” in October 1943.

On October 8, 1943, Bertholf’s string of missions began with a raid on shipyards near Bremen on the northern coast of Germany. The antiaircraft fire was thick. Bertholf recalls, “it’s just like you read, just like you read in the books, you know, or see in the movies or something’ and here we are, right in the middle of it. And we got through it…we got a whole bunch of hits that they had to fix.” On the success of the mission, Bertholf remarked “probably not” when asked if he hit the target. The flak was too great, and the altitude was too high.

The next day, Bertholf flew to Marienburg to bomb an aircraft factory. This would be the farthest mission undertaken to date, and they would bomb from 12,000 feet rather than the 25,000 at Bremen. We “creamed ‘em,” Bertholf remembers. Photos showed direct hits throughout the target area. Leadership from Bomber Command all the way up to Winston Churchill sent their congratulations to the units involved.

On October 10, in an ambitious undertaking, the 100th was ordered out for the third day in a row. The target was Munster. Of the 18 aircraft assigned from the 100th, one did not take off, four—including Bertholf’s—returned due to mechanical issues, and twelve were lost over Munster. Only one plane returned from Munster. A B-17 nicknamed Royal Flush piloted by Robert “Rosie” Rosenthal. From the 100th Bomb Group alone, Eighty-two men were captured and 37 killed. Losses at that rate would quickly become unsustainable for the 8th Air Force.

When Bertholf first arrived in England in September 1943, he heard a rumor about the 100th. “All they do is fly submarine patrols.” After Black Week, Bertholf saw the man who uttered the rumor. Not holding back, Bertholf said, “you S.O.B! Where is this submarine patrol business?”

A reconnaissance photo showing the aftermath of the Marienburg Raid. Only one building escaped a direct hit. Lt. General Ira Eaker called Marienburg “a perfect job” and “a day to remember in the air war.”

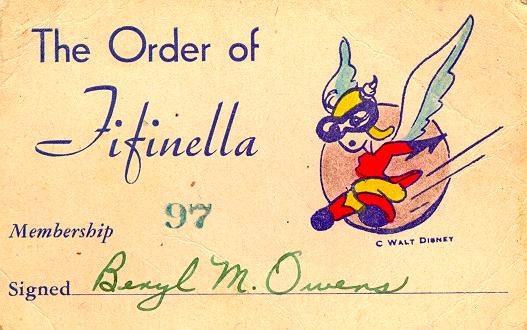

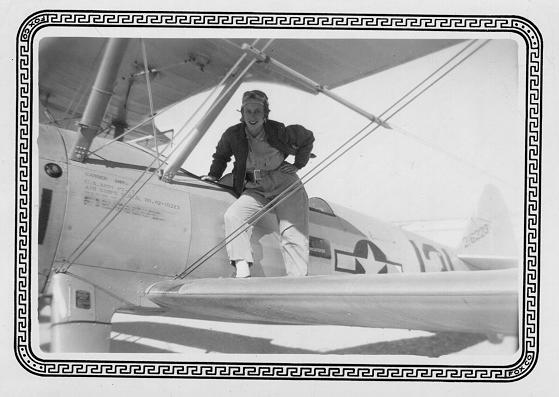

There are little to no photos available of Bertholf but there is this card noting his award of the Distinguished Flying Cross that misspelled Harlingen, TX as Harlington, TX.